Maternal mortality rates (Pregnancy related deaths) are climbing in the United States while improving in other developed countries. Health experts and advocates are scrambling to understand why and find solutions.

Key Points

- The rate of maternal mortality in the U.S. has more than doubled in the past few decades, even though this number has fallen in recent years around the globe.

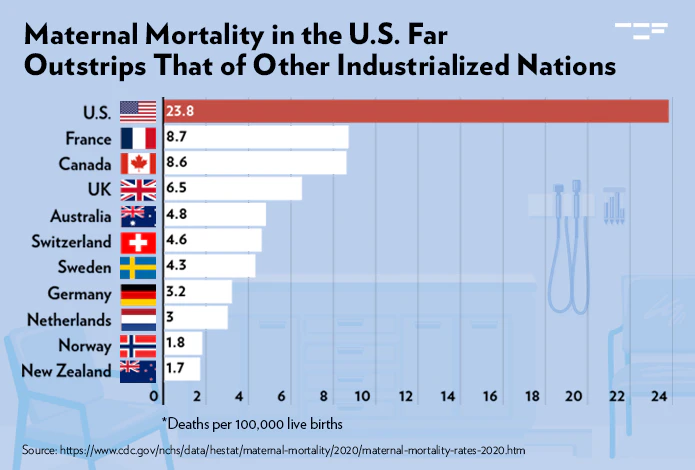

- In 2020 the average maternal mortality rate in the U.S. was twice the number seen in other high-income countries.

- Now women giving birth in the U.S. are at a higher risk of dying than those giving birth in China or Saudi Arabia.

What is maternal mortality?

The Centers for Disease and Control (CDC) defines maternal mortality as a death during pregnancy or within 42 days of the end of a pregnancy.

The maternal mortality rate, which is based on the Center for Diseases and Control (CDC) statistics data, is the number of maternal deaths per 100,000 live births.

In 2021, the U.S. had an overall maternal mortality rate of 32.9 per 100,000 live births compared with 23.8 in 2020 and 20.1 in 2019 and 12 in other developed countries.

A new study published this summer in JAMA shows how the U.S. rates defy the improving global trend.

From 1999 to 2019, maternal mortality—defined in the study as a death during pregnancy or up to a year afterward—more than doubled in the U.S.

According to a CDC report, over 84% of these pregnancy-related deaths were preventable.

At-risk populations

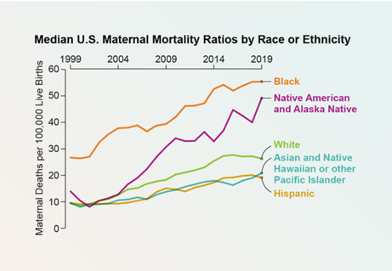

Although deaths increased in people of all races and ethnicities, some differences were seen among racial and ethnic groups.

Black women face a much higher risk of maternal death—there were 69.9 deaths per 100,000 live births in the U.S. in 2021.

Native American and Alaskan Native communities also showed a steep rise in mortality rates over the past two decades.

Credit: Amanda Montañez; Source: “Trends in State-Level Maternal Mortality by Racial and Ethnic Group in the United States,” by Laura G. Fleszar et al., in JAMA, Vol. 330, No. 1; July 3, 2023

Possible Reasons

- Poor health before pregnancy – Studies show that more women in the U.S. have pre-existing health problems such as high blood pressure, diabetes and other chronic diseases which could put them more at-risk.

- Age – The median age of mothers giving birth rose from 27 in 1990 to 30 in 2019, according to U.S. Census data. Health risks increase as we age and there are more older women giving birth.

- Covid-19 Effects – A quarter of maternal deaths were associated with COVID-19 in 2020 and 2021 combined, according to a report in October 2022 by the U.S. Government Accountability Office.

- Weight Issues -More than half of the women in the U.S. who become pregnant are above a healthy weight, which puts them at-risk for complications after delivery.

High Risk Timing

The riskiest time [for mothers] often comes after the baby is born. Yet most of the clinical and policy interventions we’ve seen in the past decade focus on improving care at the time of delivery and neglect the time before or after,” says Lindsay Admon, an obstetrician-gynecologist at the University of Michigan Medical School.

In fact, over the past decade, maternal mortality during labor and delivery has decreased in U.S. hospitals across people of all ages, races and ethnicities, as a result of improvement in birthing procedures and protocols.

Experts say most of the maternal deaths happen shortly after giving birth, when many women are forced to return to work and are unable to continue with post-partum care.

Final Thoughts

Many mothers are forced to ignore early signs of health concerns. Some mothers, even those with health insurance, can be discouraged from seeing a doctor post-partum because of the fear of high costs. As a result, they may wait until their conditions worsen, which in many cases might be too late.

“Women are saying, I can’t come in for this bleeding, for this headache, because I don’t have the support afterward,” said Dr Rochanda Mitchell, a Howard University physician who specializes in maternal-fetal medicine and high-risk pregnancies.

“During the pregnancy everybody is there, celebrating the pregnancy,” she added. “But if most of our mothers are dying after delivery – then we need help after delivery.”

For more information, read this article from Yale Medicine News.

Image by Freepik

Thank you, You will be automatically subscribed to the our newsletter.